4.4 – Pressure Measurement¶

4.4.0 – Learning Objectives¶

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Understand the difference between gauge, atmospheric, and absolute pressure.

- Know the different ways pressure can be measured.

- Understand how manometers and Bourdon gauges operate.

4.4.1 – Introduction¶

Pressure measurement is vital to any process. Measuring pressure can give you a lot of information about your system. We will go over different types of pressure, and ways to measure pressure.

4.4.2 – Gauge vs. Absolute Pressure¶

Absolute pressure is a measurement of pressure with a perfect vacuum as a reference point. This means that absolute pressure can never be negative. Gauge pressure is a measurement of pressure with the ambient air pressure (atmospheric pressure) as a reference point. This means that gauge pressure can be both negative and positive.

A similar example to gauge and absolute pressure is Celsius and Kelvin. Kelvin uses absolute zero as its reference point. This means that you can never have negative values of Kelvin. Celsius uses the freezing point of water as its reference point. This means that Celsius can be both negative and positive.

The equation used to relate gauge, atmospheric, and absolute pressure is:

where

4.4.3 – Ways to measure pressure¶

Manometers¶

Manometers are one of the most common tools used to measure pressure. As specified in Module-1, they are simple to use and can give you instantaneous feedback on your system. There are three main types of manometers, open-end, differential, and sealed-end.

Attribution: Said Zaid-Alkailani & UBC [CC BY 4.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)]

As you can see, open-end manometers have one end connected to a line or system and the other end open to the atmosphere. Open-end manometers measure gauge pressure. Differential manometers have each end connected to the same line and measure pressure drops. Differential manometers measure differential pressure. Finally, sealed-end manometers have the one end connected to a line or system and the other end closed to the near vacuum. Sealed-end manometers measure absolute pressure.

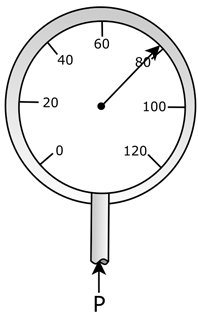

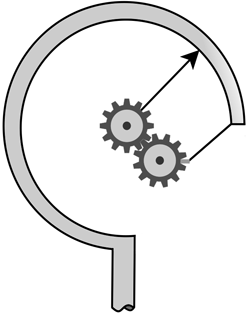

Bourdon Gauges¶

Bourdon gauges are the most common mechanical devices used to measure pressure. A bourdon gauge is a hollow metal tube that is closed at one end and bent into a C configuration. The open end is exposed to the fluid whose pressure is being measured. As the pressure increases, the tube tends to straighten to equalize the pressure in the tube. This straightening causes gears to turn which in turn will cause a pointer to rotate which will inform you on its pressure.

Attribution: Said Zaid-Alkailani & UBC [CC BY 4.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)]

4.4.4 – Problem Statement¶

Problem 1¶

Question¶

An open-end manometer, shown below is used to measure the pressure of the stream. If \(d_1 = 1.0 \space m\) and \(h = 0.7 \space m\), what is the absolute pressure at \(P_1\)?

Attribution: Said Zaid-Alkailani & UBC [CC BY 4.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)]

Answer¶

Sine we know \(d_1 = 1.0 \space m\) and \(h = 0.7 \space m\), we can solve for \(d_2\)

next we can use the general manometer equation to solve for \(P_1\)

Since the density of air, relative to the other terms, is practically 0, we can ignore \(\rho_2\).

Problem 2¶

Question¶

A U-tube manometer is connected to a closed tank. The air pressure inside the tank is 0.50 psi and the liquid is oil (\(\gamma\) = 54.0 \(lb/ft^3\), S.G. = \(3.05\)). The pressure at point A is 2.00 psi. Find

- the depth of oil

- the reading \(h\) on the manometer.

Note: that the 2’ above the 2. does not mean 2 prime, it denotes 2 feet.

Answer¶

a) Note: We are using (1.) as the reference point.

Notice that we need to convert all units to a single uniform unit:

b) Note: We are using (1.) as the reference point.

In [ ]: